I recently read the book The Enchanted Hour (Gurdon, 2019) in which the author recalls what novelist Kate DiCamillo once said to her:

‘We let down our guard when someone we love is reading us a story … We exist together in a little patch of warmth and light’.

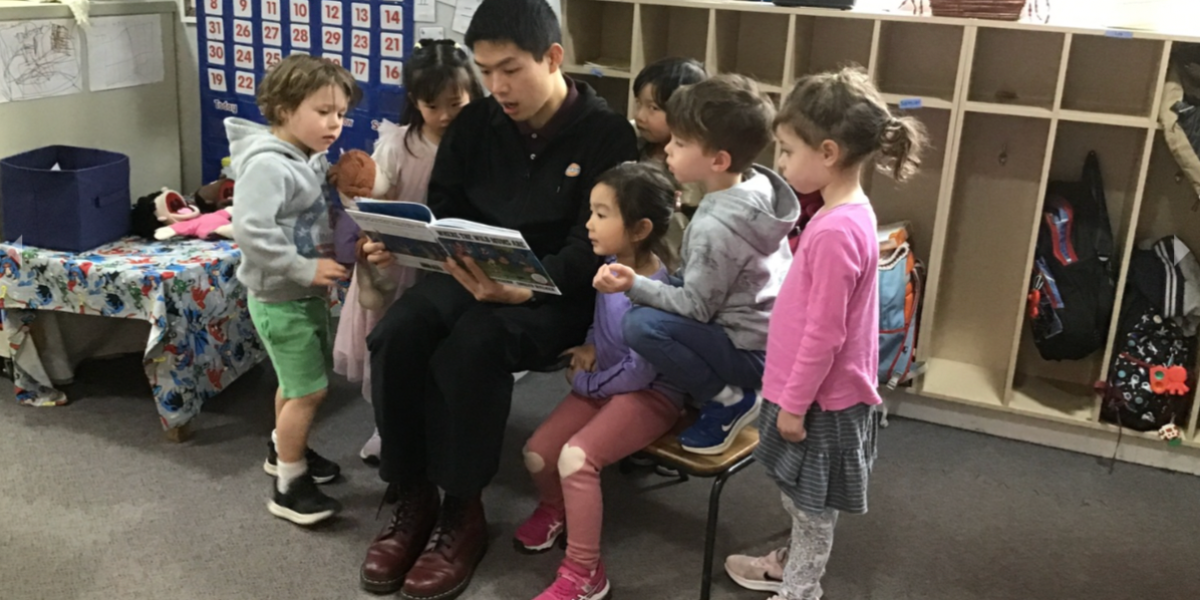

Image: supplied, Darren Halim

These words resonated with me and got me thinking about the hidden and ever-pervasive power of reading aloud to children. They even took me back to my student days and reminded me of the moment during my teacher training course when a lecturer emphasised the power reading books aloud has on children’s creativity, literacy, relationships and overall learning development.

The benefits of reading aloud have been overwhelmingly supported by research (Anderson et al., 2003; Isik, 2016; Phillips, 2000; Shickedanz & Collins, 2012; Suggate et al., 2013) and social scientists now consider read-aloud time as one of the most important factors in providing children with a positive start to their lives (Gurdon, 2019).

As I have progressed in my teaching career, however, I have noticed this traditional teaching method does not always receive the focus it deserves. Reading books to children is sometimes regarded as too simple a task for teachers. Perhaps this thought pattern stems from an unspoken insecurity where teachers feel like they’re not doing enough for the children and need to think of something more creative or entertaining with a more novelty punch. Or, perhaps reading books aloud has slowly lost its place in the digital age of distraction because it means sacrificing time (Gurdon, 2019) for something else in the children’s daily routine.

Let’s compare reading with other learning experiences in the digital age.

Reading books aloud vs visual media

Internet and technology use has irrevocably changed the way that early childhood services operate. Although the use of visual media can enhance the learning gained from reading books aloud, research suggests that these two forms of learning do not stimulate the child’s brain in the same way (Gurdon, 2019).

Watching movies and engaging in screen time tends to be more of a solitary activity, unless it is specifically designed and planned to be interactive. Conversely, reading aloud is usually a group activity or has the ability to draw children together if teachers are only reading to one or two children at a time. This shared enjoyment creates a natural space for imaginative interaction and engagement with others (Suggate et al., 2013).

Screen time can also leave children feeling overstimulated and unsure of where to direct their surplus energy. Listening to a story can settle their minds and bodies, helping their brains engage in deep and sustained attention (Gurdon, 2019).

Studies have shown that brain activity in children changes according to the type of learning experience they are engaging in. A higher number of neurons fire in children’s brains when they are listening to a story, compared to when they are watching a movie or engaging in screen time (Gurdon, 2019).

The developing brain and behavioural science

Listening to stories, especially while looking at pictures, stimulates children’s deep brain networks and fosters their optimal cognitive development (Gurdon, 2019). When children have stories read to them on a regular basis, they are more likely to grow into adults who enjoy strong relationships and have a sharper focus, greater emotional resilience and better self-mastery (Gurdon, 2019; Shickedanz & Collins, 2012).

Children who are read aloud to more often and who have access to a range of books show higher levels of receptiveness as well as the ability to understand literacy and language (Phillips, 2000). They also display higher creativity and imaginative capability, as they can visualise mental images (Gurdon, 2019). This is important during early childhood, as a child’s brain has high levels of plasticity from birth to the age of eight years, and a significant amount of growth and development occurs during this phase (Gurdon, 2019).

Gurdon (2019) explains that the companionable aspect of shared reading fosters learning dispositions such as empathy and curiosity. Reading aloud is a gateway to a diverse range of vocabulary development and a pathway to early reading skills (Suggate et al., 2013). As a teaching tool, stories can cultivate children’s understanding of sentence structure, consolidate new phrases and vocabulary, encourage rhythm and punctuation practice, and familiarise children with different contexts (Isik, 2016).

Not surprisingly, adults can also benefit from the practice of reading aloud whether they are the reader or the listener. Our attention is so often pulled in endless directions. Slowing down and taking the time to read to a child or listen to a story can be an effective restorative exercise.

So, how might teachers go back to the basics with reading time?

Reading books aloud is an excellent tool and one all teachers should feel encouraged to use strategically for providing meaningful learning. Teachers can use the planning cycle to map out their learning intentions and assess and reflect on the learning outcomes achieved. As well as reading the story, teachers can consider possible learning extensions such as staging the learning environment and extending on themes that spark the children’s interest (Anderson et al., 2003; Phillips, 2000).

Oral storytelling and silent reading are two other ways of exploring the possibilities of early literacy. Both provide significant benefits to all age groups, and engaging in a variety of storytelling methods is encouraged for meaningful learning experiences (Suggate et al., 2013).

Anderson, J., Anderson, A., Lynch, J., & Shapiro, J. (2003). Storybook reading in a multicultural society: Critical perspectives. In A. Van Kleeck, E. Bauer, & S. Stahl, On reading books to children: Parents and teachers (pp. 195–220). L. Erlbaum Associates.

Gurdon, M. C. (2019). The enchanted hour: The miraculous power of reading aloud in the age of distraction. Piatkus Publishing.

Isik, M. A. (2016). The impact of storytelling on young ages. European Journal of Language and Literature Studies, 2(3), 115−118.

Phillips, L. (2000). Storytelling: The seeds of children’s creativity. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 25(3), 1−5. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693910002500302

Shickedanz, J. & Collins, M. F. (2012). For young children, pictures in storybooks are rarely worth a thousand words. The Reading Teacher, 65(8), 539−549. https://doi.org/10.1002/TRTR.01080

Suggate, S. P., Lenhard, W., Neudecker, E., & Schneider, W. (2013). Incidental vocabulary acquisition from stories: Second and fourth graders learn more from listening than reading. First Language, 33(6), 551−571. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142723713503144

ECA Recommends: Resources to use with children

Find a range of specialty and educational books for children, covering topics such as reconciliation, body autonomy and consent, children with additional needs and inclusion. From picture books for infants to educational books for toddlers, through to books for older children, we have books and resources to introduce sensitive or tricky topics at all ages.